Background

The retirement investing approach most commonly advocated by financial planners is based on the assumption of spending down capital through retirement so that neither is a lot left over nor does it run out. It is well suited to the standard type of retirement accounts such as traditional IRAs and 401(k)s, since the IRS requires these accounts to be drawn down anyway.

Outside of such required schedules the financial planning industry has advocated alternatives like the “4% rule”, which boils down to spending 4% of your portfolio value in the first year of retirement, and adjusting the amount by the CPI annually thereafter. This model is rife with problems. First, once the withdrawal pace is set, there is no feedback mechanism to adjust it for a changing world over the course of decades. For all the planning, a lot of ad hoc adjustment is going to be needed anyway. The 4% figure itself has come under scrutiny, with many now advocating a 3% rate or even lower, to reduce the possibility of running out of money. Second, you don’t know how long you’re going to live or how the markets will perform. Withdrawal rates are based on statistical life expectancies, historical markets performance and Monte Carlo simulations. While statistics can represent the average retiree, very few retirees actually expire right on schedule, so it’s almost assured to be wrong for you as an individual. And I don’t know about you, but playing Monte Carlo with my life savings isn’t very appealing. Third, it makes no provision for leaving a legacy for heirs. Finally, there is “sequence of returns” risk … the added stress of worrying about wild fluctuations in what your investments could be sold for … because you’re depending on selling them.

In short, it attempts to make your investment portfolio act like an annuity … income that lasts as long as you live then is gone. Yet you probably already have an annuity … Social Security is one example. Some may have a pension, and even those who don’t have the option of converting some of their accumulated assets into one sold by an insurance company. So trying to shoehorn your entire life savings into a messy annuity-like model not only can’t safely and accurately be done, but it reduces your diversification among strategies. It’s like having a dog and a cat and trying to convert your cat into a dog. Why? You already have one.

I prefer to let annuities be annuities and portfolio assets be portfolio assets. Most of us are best off with some of both.

Some portfolio assets are best suited for generating income without having to be depleted. And by this I mean investments in an ordinary brokerage account or Roth IRA. Recall the IRS will require you to draw down your traditional IRA, so the following does not apply there. What follows is best for regular taxable accounts and Roth accounts.

You can structure a portfolio that yields in excess of the more recently recommended “safe” withdrawal rates and which yield should grow in excess of inflation over time as well. For this portion of your retirement, there is also no risk of outliving your money because you won’t be selling off your shares. For the same reason, you’re also freed from worry about what will happen to market prices and the risk of having to sell low.

The Portfolios

Model income portfolios designed for that purpose are illustrated at Model Portfolios. Let’s talk about the funds listed and why these particular combinations.

GOVT is the iShares US Treasury Bond ETF. It covers the entire nominal US Treasury market from one to thirty years maturity.

VT is the Vanguard Total World Stock ETF. It covers the entire world stock market, with nearly ten thousand stocks.

For a simple, modest, portfolio, US investors could stop there. But we can improve the stock allocation it by tilting the field towards dividends, quality and value. Another way to say it is starting with the world stock market and underweighting the shares of supersized companies that don’t pay dividends, and throwing out the junk that is overpriced or poor quality. What remains is still exceptionally broadly diversified.

DTD is the WisdomTree US Total Dividend Fund. It receives the lion’s share of the US stock allocation. It essentially covers the entire US stock market, except that rather than being weighed by market cap, it’s weighted by dividend stream. It aims to own each stock in proportion to the aggregate dollar amount of dividends expected to be paid over the following year. It does not include stocks that don’t pay dividends, such as Alphabet, Amazon, Meta Platforms, and other supersized nondividend payers. It does include Apple, Microsoft, and even Nvidia, although at much reduced weights as compared to market cap based indices. This reduces dependency on potentially overextended areas of the market.

It would be nice if WisdomTree offered an XS (ex-US) counterpart to DTD. But it doesn’t. The closest it comes is DNL, the WisdomTree Global ex‐US Quality Dividend Growth Fund. It is also a dividend weighted index, but is screened for growth. Its largest holding for example is the company that actually makes Nvidia’s chips, Taiwan Semiconductor.

IQDF is the FlexShares International Quality Dividend Fund. It balances the growth oriented DNL with a value orientation … the combination more closely resembling what that missing DTD counterpart might look like.

The intent is not to entirely exclude nondividend paying stocks. Today’s small cap companies can become tomorrow’s big dividend payers, and can even further broaden and balance stock market exposure. VFQY is the Vanguard US Quality Factor ETF. VFVA is the Vanguard US Value Factor ETF. These are actively managed funds that include several hundred stocks each, but feature Vanguard’s trademark low expenses. VFVA in particular sports a dividend yield competitive with DTD, with a higher historical growth rate. VFQY complements it by including a higher allocation to growthier sectors like tech, balancing out sector exposure. Impressively enough, though, VFVA has actually grown dividends faster, inspiring its higher weighting in the mix. These are both all-cap funds but notably tilted towards small caps. And both have both a higher yield and a higher dividend growth rate than the US stock market as a whole.

SCHD is Schwab’s US dividend fund and SCHY its XS counterpart. SCHD has an impressive track record in both current yield and dividend growth. This is likely due to what might be considered a quasi-active nature; while not actually actively managed its selection criteria are designed to add value as opposed to merely track a market segment. SCHY doesn’t have enough history to properly evaluate though, and has an added volatility screen and weird structural cap on promising emerging markets that could dilute the value added by SCHD’s selection criteria. In addition it pays dividends only semiannually. Being limited by design to around 100 stocks each, these funds are bit specialized for large core positions but make excellent augmentations. To compensate for the systematic SCHY underweight in emerging markets, we add a small position in VWO. A small position in micro cap IWC rounds out the US fund allocation.

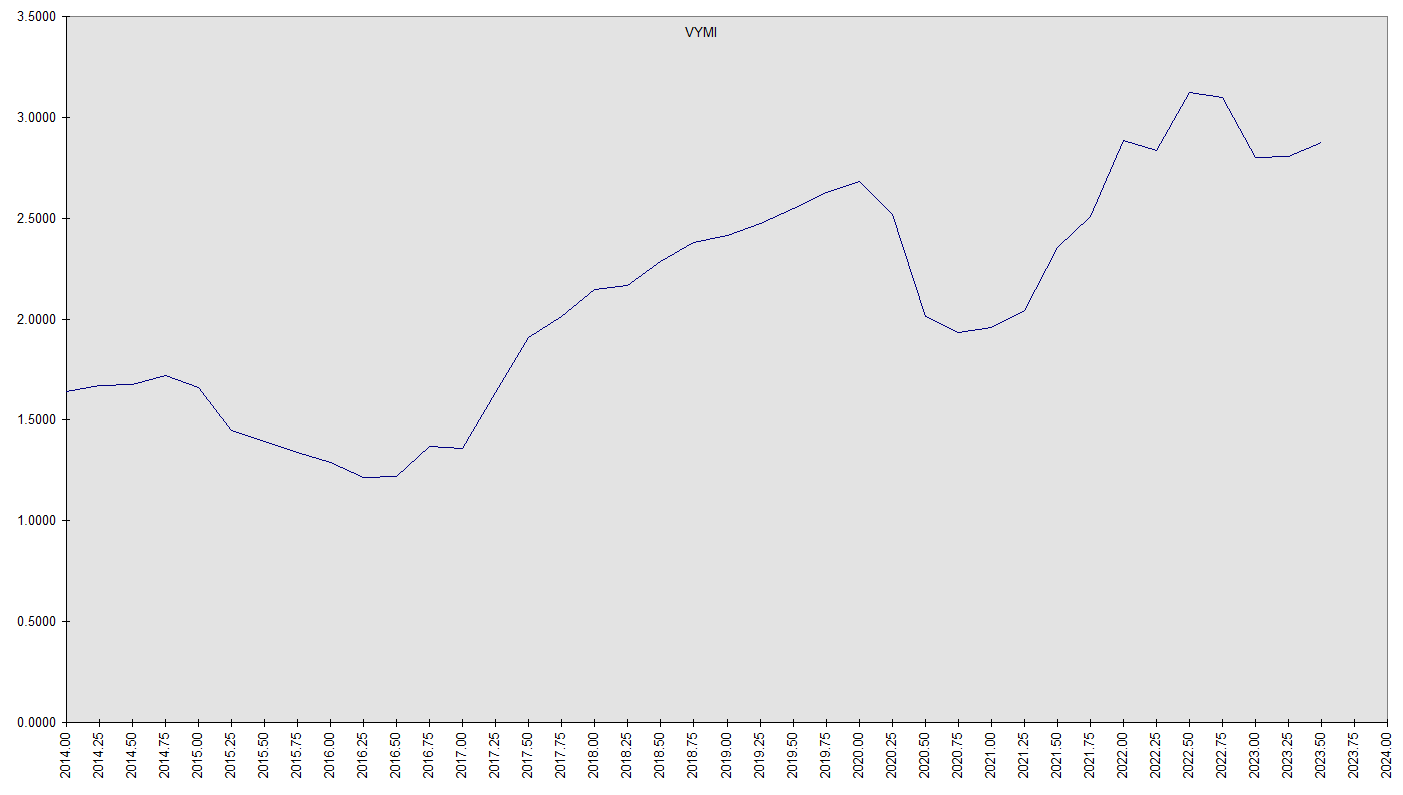

VYMI, the Vanguard International High Dividend Yield ETF, replaces VXUS in earlier versions of the Model Portfolio. This is another example of strikingly value added selection. Typically one faces a tradeoff in dividend investing. You can have a high yield or you can have a growing yield. This fund starts with the same stock universe as VXUS – the entire world ex-US – but has demonstrated both a higher yield and a higher dividend growth rate since its inception. It is also very broadly based, including well over a thousand stocks with the top ten accounting for less than 15% of its value. It has also significantly outperformed its universe on a total return basis. VYM is its US counterpart.

This leaves just XS small caps. All of the above ex-US funds underweight or exclude them. VSS, the Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US Small-Cap ETF, fills this gap.

So our list now covers the entire global stock market with special emphasis on dividends, quality and value.

Let’s dig deeper still. Being an otherwise outstanding fund, VYMI inexplicably excludes REITs. This is a structural defect; according to Vanguard’s web site: “Excludes REITs, which generally do not benefit from currently favorable tax rates on qualified dividends.” We want our portfolio to be broadly balanced by geography, sector and market cap, so we don’t want such structural omissions in coverage having nothing to do with a fund’s investment objective. (We don’t buy Vanguard’s excuse since many of its other funds, as well as those of its competitors, include REITs). So we have a hole to patch up. Oddly, Vanguard no longer offers a REIT fund capable of filling the gap. Its ex-US real estate fund, VNQI, is not a REIT fund, including not only REITs but non-REIT real estate companies as well. So using VNQI would introduce an overlap duplicating coverage of non-REIT real estate stocks.

It also turns out that, even though the fund materials don’t say they exclude REITs, our two Vanguard US funds, VFQY & VFVA, apparently do exclude them, based on a review of their holdings lists and realty sector underweights. And Vanguard’s US counterpart to VNQI, VNQ, was a few years ago expanded to also include non-REIT real estate, leading to the same messy overlap and duplication problem if you tried to use it to plug the hole. As a result these three Vanguard funds are all underweighted in real estate due to structurally excluding REITs, and Vanguard’s fund lineup offers no clean patch. In short, Vanguard has several funds that exclude just REITs but no funds that include just REITs

This is where REET, the iShares Global REIT ETF, comes in. Our position in VYMI however is larger than in VFQY-VFVA, so that only would leave us either underweight ex-US realty or overweight US realty. VSS to the rescue once again … it is solidly overweight realty relative to the overall XS market, due to REITs being primarily smaller cap stocks, balancing out the deficit. The share proportions listed above take this carefully into account; in fact, given that this is an income-oriented portfolio and REITs are important income-producing investments, we’ve added a bit more just for good measure. If you are already heavy in real estate elsewhere, feel free to reduce it a bit.

That leaves COMT, the iShares GSCI Commodity Dynamic Roll Strategy ETF. Commodities are a vital part of any investment portfolio. COMT fills this niche. Tweak exposure to circumstance and taste.

More about the fund selections

Besides broad, balanced and inclusive coverage, a key part of these fund selections is based both on current yield and potential growth of that yield. It’s often the case that investors face a tradeoff between them. Most dividend funds are marketed either as high dividend or dividend growth funds. That is, you can either have a generous current income or a growing income, but not both. Dividend growth funds furthermore tend to look for that growth in the past; for some for example the main stock selection criterion is ten or twenty five years of increasing payouts. Thanks, but we can’t collect past dividends. The best dividend growers of the future are not necessarily those of the past. The result is that for their lower current yields, dividend growth funds haven’t necessarily produced more dividend growth. As we’ve seen, several of our fund selections offer both more attractive current yields and, at the fund level where we care about it, more attractive dividend growth than the competition.

We of course don’t know how the financial markets will perform in the future, but we can compare the historical performance of funds with each other, looking for relationships that are likely to hold. If fund X and fund Y for example both fish in the same lake, but fund X has consistently reeled in a better combination of cash flow and cash flow growth, we suspect that will continue to be the case, especially in these types of funds where the selection and weighting criteria are primarily algorithmic. This is a more substantial use of historical data than simple past returns, which can reflect recently inflated prices. So instead we’ve used the dividend history to project future dividends.

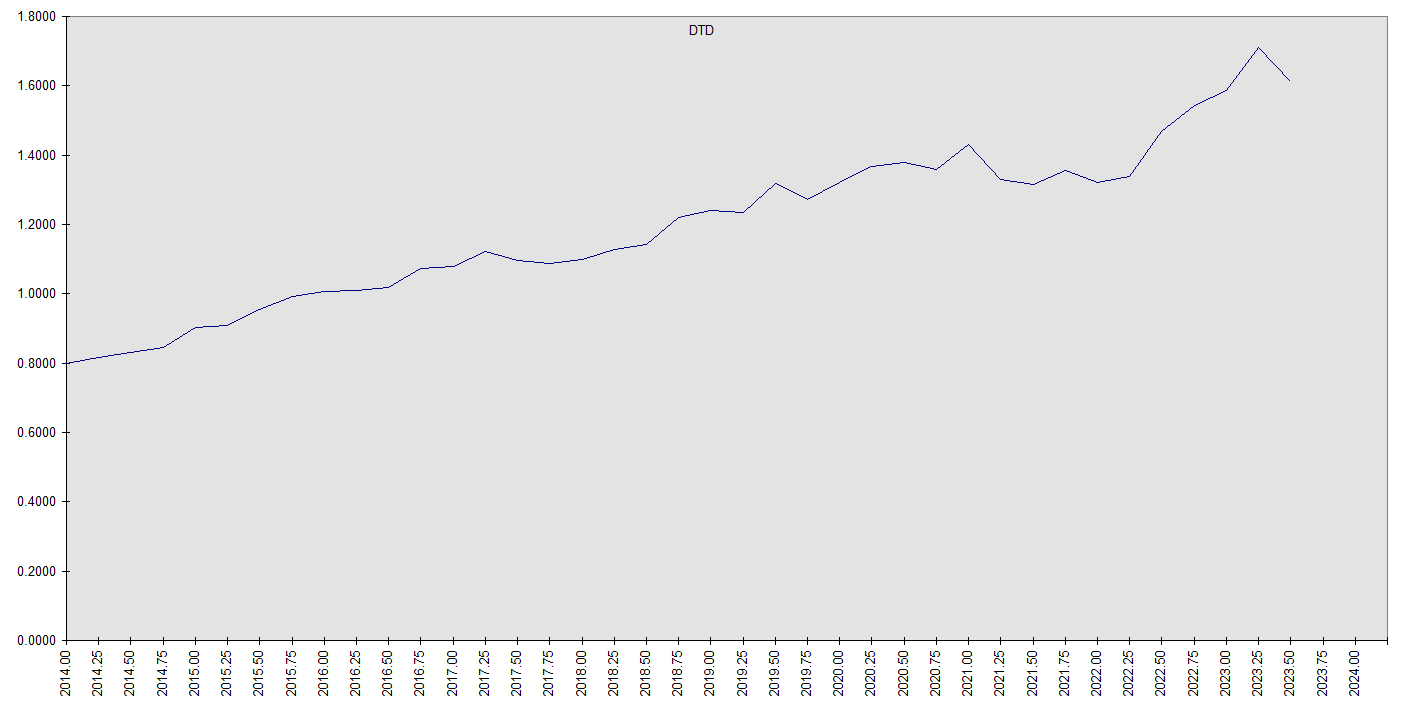

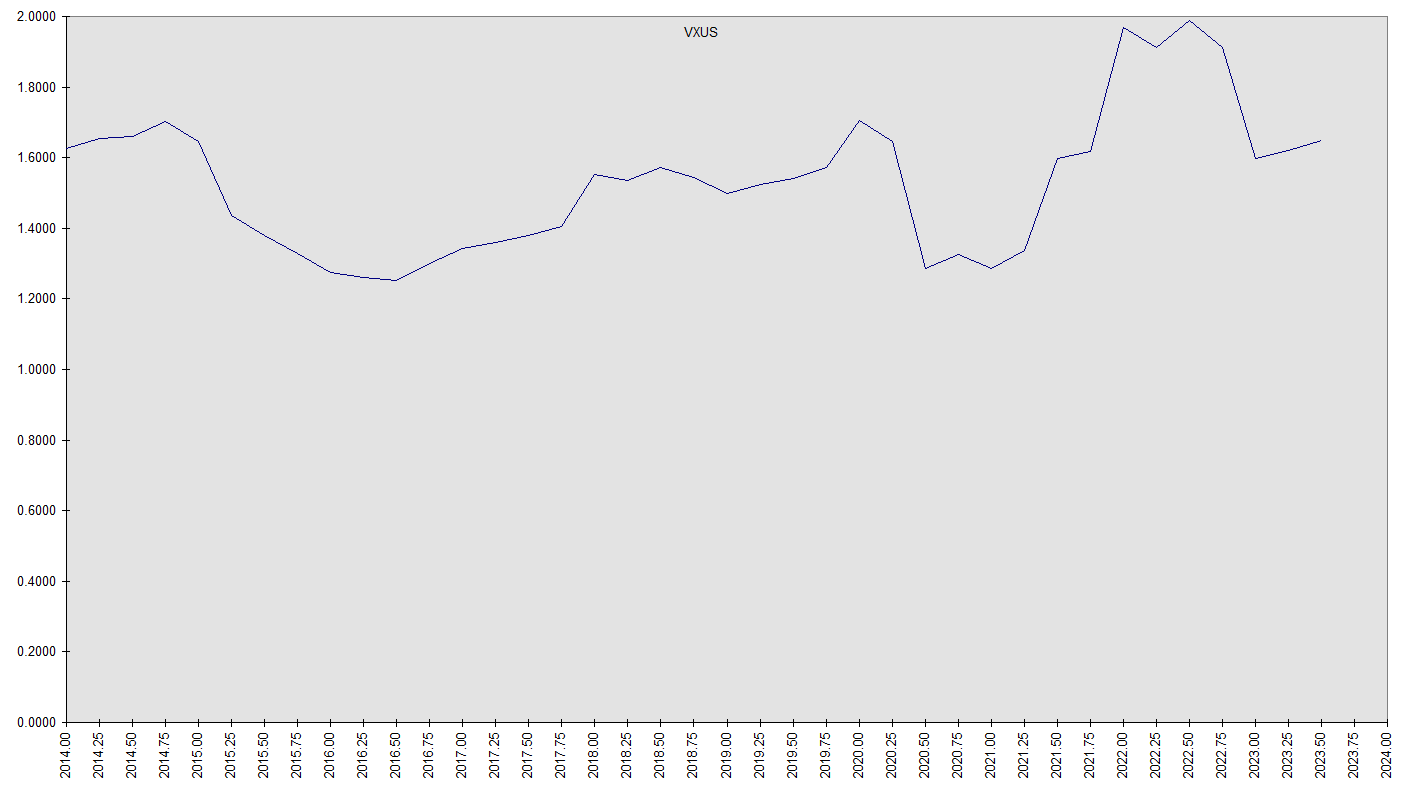

One use of this data is to sum the expected dividends over the next four years and divide by the current price to find an expected forward yield. VYMI for instance is projected to pay an average of $3.66 per share from 2024 to 2028. At a recent price of $62.56, this amounts to a 5.85% yield. Compare that to VXUS, which is expected to pay $1.70, which at a recent price translates to a 3.08% yield. This reflects both a current year expected VYMI yield of 4.78% and a payout growth rate of 7.97%, compared to a VXUS current year yield of 2.99% and a growth rate of 1.18%. Even when broadened and balanced with the missing small caps and REITs the VYMI composite forward yield comes out to 5.26%. Hence our earlier value added observation. Again, while this doesn’t tell us what those dividends will actually be, it does give us some insight into how funds operating in the same investment pool are likely to perform relative to each other. The following charts of the dividend history for two of the funds, with two others representing their investment pools, help illustrate:

Notice the distribution growth rate of DTD actually exceeds that of its US stock lake represented by VTI and the growth rate in VYMI even more strikingly exceeds that of its XS counterpart lake in VXUS. That these funds do this while also sporting substantially higher current yields is impressive. Notice also how the dividend payments surged with the recent inflation.

Among the stock funds, little or no rebalancing should be necessary. Over time the best performers will grow to be a larger proportion, increasing their weighting, automatically improving the mix.

Conclusion

This is not only not an ideal portfolio for everyone; it’s not even a complete solution for anyone. Most also need a stash of savings for liquidity … to cover occasional expenses like a new car, vacation, medical care or unexpected emergencies. This would include cash and precious metals as well as stocks and bonds. Those might be more appropriate for your traditional IRA, your safe deposit box, or buried in your back yard. This is the objective of the Capital Portfolio listed on the Model Portfolios page. The income portfolios are however aimed at providing a long term growing stream of income based on a broad foundation of assets, including US treasuries and global stocks diversified and balanced by geography, sector and market cap. Think of it as an ETF made up of other ETFs … ideally we would like a stock fund that owns all the world’s stocks but weighted by dividends, quality and value rather than market cap. They’re not being such a thing, we’ve pieced one together from off-the-shelf parts. Once set up, it should require very little ongoing attention. Just collect the income. It’s meant as a complement to an annuity income and traditional IRA drawdown portfolio.

Finally, some general comments on constructing a fund portfolio. Too often the temptation is for investors, especially novices, to scan lists of top performing funds for ideas, and then compare them based on their historical returns. Every prospectus or fund document that lists such returns includes a requisite disclaimer to the effect of “past performance does not indicate future returns”. This may be boilerplate, but there are no truer words in finance. For any prospective investment, it is far better to understand what the fund holds and how it selects it. The most important information a fund issuer presents is in what asset class it invests, what geography, what sectors, what style, what market caps. What are the expenses. What are its holdings. And most of all, how do they relate to your investment objectives. The all important issue is how it fits together with other investments … a strong portfolio is not just a collection of isolated strong assets, it’s a gestalt thing.