Why Invest?

It’s the way it works. When we’re young and able bodied, we labor. Along the way, we accumulate capital, so that when we’re not quite so young and able bodied, we can retire. To do this, we need to save. Saving means setting aside some of your current income for the future. For this purpose you need some way to store value. The simplest form for most people is cash. You could take some of your money and put it under the mattress, and then take it out at some point in the future. Money is something that economists define as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value. The best medium of exchange and unit of account, however, may not necessarily serve as the best store of value.

Putting your money under the mattress may seem like the safest possible thing to do with it. After all if you put $1000 in, it will still be worth $1000 when you take it out. Guaranteed. But unfortunately this safety is mere illusion. This is because you’re using the same unit to measure the thing you’re measuring. Fallacy by tautology … $1000 dollars is always worth $1000.

Over short periods of time, your safety assumption is likely correct; $1000 tomorrow can buy just about the same amount of stuff (food, clothing, utilities, rent, medical care, etcetera) it does today. But in a year, ten years or more? You’re much more likely to notice the difference. In ten years, the same number of dollars might only be able to buy half of what it could today. This exposes the illusion … in fact your unit of account is losing value. Because the dollars are losing value, it takes more of them to buy the same stuff. Inflation … your government and banking system is increasing the supply of money and so it is depreciating. This apparently risk free way of saving is almost guaranteed to be a loser. It leaves you 100% exposed to inflation risk.

As an alternative, you could put your money in the bank. This way it will earn interest, and possibly compensate for the loss of value due to inflation. For much of US history, this worked. The rate of interest banks paid on savings was comparable to the rate at which dollars lost value, often more. But in recent years the rate of interest has fallen far below the rate of inflation. Your bank may pay 0.01% or so interest, but the rate of inflation has been much higher, 1%-5% depending on how you measure it. And the issuer of the US dollar, the Federal Reserve, has practically promised to devalue it by at least 2% annually for the foreseeable future. What’s more, you will be taxed on the nominal interest you’re paid, not the real rate, so you’ll come out even further behind. So this is another practically guaranteed loser. This means that if you’re looking to avoid loss over time, you will have to consider other assets.

Is there any asset that is a safe store of value? Unfortunately not; there is a tradeoff. Those other assets may be more effective for storing or even building value over the long run, but in the short to medium term could be big losers. Just the opposite as with your dollars. Sometimes these other assets can decline over periods of years. But just as with dollars, if you used any of them for your unit of account you wouldn’t directly notice any change in its value at all. The point here is that dollars are securities too, and like other securities, their value fluctuates. Their appearance of stability is merely an artifact of our habit of using them as our measuring unit of value.

But all is still not lost, since we haven’t yet considered the possibility that some combination of assets might qualify pretty well as a safe long term store of value. And in some cases even allow you to get ahead by paying you rent on your capital in the form of interest or dividends as you go along.

The Global Market Portfolio

What if you could own some proportional slice of everything in the world? No matter what happened, you couldn’t fall behind. Since you own a representative portion of all assets, regardless of its value in dollars (or whatever you use for your unit of account), in a very real way you’ve assumed the lowest possible risk of loss due to your selection of assets. You have less risk of loss than if you owned just dollars, just real estate, just stocks, just bonds, just gold, or just about any other one thing you could have chosen. So this mix, sometimes called a “global market portfolio”, is a benchmark for real investment safety.

At what level would this apply? Since the global market portfolio is an all inclusive aggregate, then its individual counterpart would be total net worth. That is, for benchmarking purposes you would count not just your financial assets, but the value of all property such as your home (as real estate). Debt would count as a negative position in bonds, so your effective bond allocation would be your investment position minus your debt.

Of course there is no practical way to own a proportional slice of everything in the world. Most assets are privately owned, not publicly traded; a familiar example might be your own home. There are ways of approximating it, however, using things that are publicly traded, for example exchange traded funds (ETF). A number of analysts have proposed ETF portfolios that aim to do just this. A good example is the “Almost Everything” portfolio described at Pension Partners, Searching For the Market Portfolio. This could serve as a starting point for a large investment portfolio. The number of funds may be impractical and unwieldy for most individual investors, however. In addition, for those who already own their own homes or other real estate, the dedicated real estate stock exposure (real estate stocks are already covered by the broad stock fund) would be unwanted overlap. All real estate is different, and even publicly traded real estate and privately held real estate as a class can diverge markedly, so just adding more publicly traded real estate to compensate for the absence of private real estate is questionable, and in this context only appropriate for those who don’t own real estate in any other way. Our Model Portfolio Introduction will assume an investor who already owns real estate separately.

The Permanent Portfolio

A simpler approach to nest egg safety is the Permanent Portfolio, described in Harry Browne’s 1999 book, Fail Safe Investing. In effect it can be thought of as a simple approach using only four investments to approximate the performance of the theoretical Global Market portfolio. Browne developed this model with Terry Coxon to outline a strategy for protecting and growing assets. One quarter of the portfolio each is allocated to cash, bonds, stocks, and gold. Because at least one of these assets tends to do well in virtually every kind of economic condition encountered, Browne saw it as a way for investors address the problem of no one asset being a safe way to store and accumulate value. Specifically, a portfolio constructed along these lines might include 25% in a US TBill fund, 25% in a long term US Treasury fund, 25% in a US stock fund, and 25% in gold. Readers interested in further understanding the rationale behind it, along with other practical investing wisdom, should consult the book. We’ll take a look at an implementation in our Model Portfolio Introduction.

Okay, this covers virtually all the world’s stock market, but why just US Treasuries for bonds? The answer has to do with correlations between asset classes. Corporate bonds are issued by the same entities that issue stocks, and although a distinct asset class, share some of the same risks. When times are tough for corporations and stocks fall, though not to the same degree, corporate bonds are often affected as well. US Treasuries, however, are from an entirely different kind of issuer and often rise when stocks fall. This lower correlation helps reduce the volatility of the overall portfolio. Investors who prefer to go with a more comprehensive bond allocation may do so in the context of the spirit of this model portfolio, though it might increase volatility and risk a bit. (For more on this, see Treasury Bonds Are the Only Bonds You Need.).

Likewise, why not include all commodities, not just gold? Again, it has to do with correlations. You could include copper, for example, but it tends to be much more correlated with stocks than gold. And while some model portfolios omit real assets like gold completely, it’s valuable for those times when financial assets like stocks and bonds both do poorly. It’s also conveniently and inexpensively available in ETF form. Nearly one out of three years of the past fifty gold has outperformed both stocks and bonds, indicating its ability to further smooth the dips in a stock and bond only portfolio. Gold itself has been used as money for thousands of years, and while like anything else its value rises and falls, over long periods of time it has retained its value. No man-made money has ever done that.

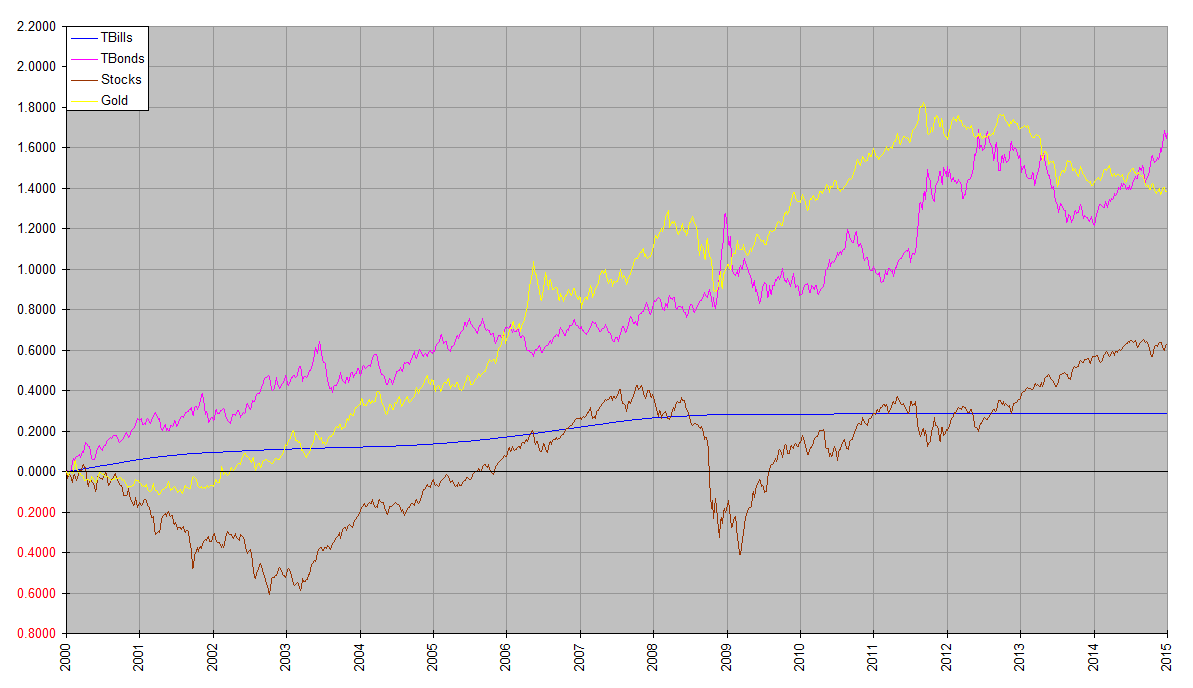

Why do correlations matter? Well, imagine you had four investments that all rose and fell at the same time. The whole portfolio would rise and fall in sync. If you needed to tap it when everything was low, you’d have to sell something low. And you may almost as well have just owned one of the investments. This is real risk. If the four investments were uncorrelated, on the other hand, it’s much less likely they would all be down at the same time, and your portfolio would rise and fall much less as well. If you needed to tap it, chances would be much better that you wouldn’t have to sell something at the bottom of a cycle. Here is a chart which shows (in dollars) the total return performance of four asset classes over the first fifteen of the millennium. Notice how these asset classes, while they increase overall, tend move up and down at different times. This is what we mean by low correlation.  In fact the true correlations are even less than are implied on this chart, because all the assets are shown priced in dollars. That means that joint movement among the asset classes reflects not some kind of metaphysical conspiracy to move together, but the fact that they all indirectly reflect the market value of the dollar itself. So in those areas where you see common decline, such as in parts of 2008-2009, it reflects a rising value of the dollar. And you also see it in the tendency of all the plots to move higher over time, reflecting in part a declining value of the dollar. And this is just what we wanted to get around in the first place.

In fact the true correlations are even less than are implied on this chart, because all the assets are shown priced in dollars. That means that joint movement among the asset classes reflects not some kind of metaphysical conspiracy to move together, but the fact that they all indirectly reflect the market value of the dollar itself. So in those areas where you see common decline, such as in parts of 2008-2009, it reflects a rising value of the dollar. And you also see it in the tendency of all the plots to move higher over time, reflecting in part a declining value of the dollar. And this is just what we wanted to get around in the first place.

Playing It Safe

As you may have gathered from the title, Harry Browne’s book, “Fail Safe Investing”, reflects a philosophy of playing it safe. It’s no coincidence that another great investor, Warren Buffett, has emphasized the same mindset. Buffett’s first rule of Investing: Don’t lose money. His second rule: Don’t forget Rule Number 1. Some might be puzzled by that … there’s always a tradeoff between risk and return, right? That’s a simplistic view that stems from assuming that risk is defined in nominal dollar units, not real value. But as we noted above, cash is just another security, and with its own ups and downs, mostly downs. As it turns out, my own experience in investing bears this out as well; usually my best gains have come when I was focused most on avoiding losses, but thinking in real, not dollar terms. So the often invoked maxim that there’s an unavoidable tradeoff between risk and return isn’t as ironclad as many would lead you to believe … if you take a holistic view of risk, risk avoidance itself is good for returns. This is what experts like Browne and Buffett are getting at. In practice playing it safe means judiciously balancing a mix of assets with complementary strengths. The model portfolios we turn to next embody that philosophy.